Dr. Rebecca Richards

Lecturer in International Relations

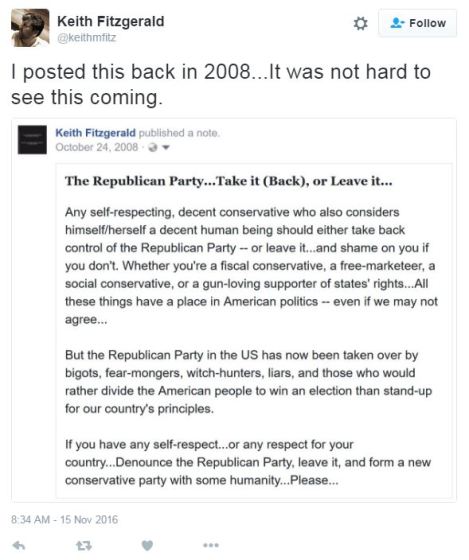

This week, I, like much of the rest of the world, have been forced to grapple with a sense of shock as I watch the post-election events shaking America. One the one hand, I am unbelievably ashamed that my country of birth appears to have regressed to social decay and violence that we are only just starting to get to grips with in post-Brexit Britain. On the other hand, I am also incredibly proud to see so many people, especially young people, peacefully protesting to say “this is not right.” So as I watch what is unfolding in the US, I watch with a sense of shock, and with trepidation as the best most of us can come with when trying to ponder what comes next is “we do not know.” I am not watching with surprise, though, because we have been able to see this coming for a long time.

Early analysis of Trump’s electoral win is focusing on economic arguments – the Rust Belt, a historically Democratic area, went to Trump, with many maintaining that it is due to the decline in manufacturing jobs and a lack of alternative employment opportunities. There is some truth to that as global economic changes and demands have seen many richer countries shifting away from industrialised labour in favour of more skilled or technological industries. Thus, those working in the once prosperous car factories of Detroit or the steelworks in Pittsburgh are facing uncertainties, and those uncertainties are both a powerful political motivation as well as something that is easy to invoke for the purposes of political mobilisation. In other words, they have genuine concerns about their future, and those concerns are easy to pick up and use as a tool in an election campaign. Trump did this masterfully by invoking, and possibly creating, a fear of what is to come.

Early analysis of exit polls, though, shows that the main core of Trump’s electoral support did not come from the low income workers in the US, but rather middle to upper middle class whites across America. Much of his support came from the old Republican base, and he was able to bring enough of the working class Democratic base in key states like Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania onto his side to win enough Electoral College votes to secure a seat in the White House. As my colleague Jon Herbert has pointed out, preventing this swing was not helped by having Hillary Clinton as the Democratic candidate. Yes, Hillary Clinton is an unbelievably accomplished and experienced public servant. However, she is also very much disliked by many, including many Democrats. She may have made a remarkable president, but she did not make a good candidate.

Still, though, Clinton won the popular vote by what would be considered in other elections a large margin.In those key areas where she lost the state and then did not gain the Electoral College votes, Trump’s majority was incredibly slight – 68,000 in Pennsylvania, 27,000 in Wisconsin, and just 12,000 in Michigan. In other words, just over another 100,000 votes in those states together and the outcome of the election would have been different (and thanks to Dr. Chris Huggins for helping point that out). Trump may have shocked us, but he did not win with a resounding victory, no matter how much he wants to claim that he won it easily and it “was big”. He will enter the White House as the least popular presidential candidate the US has ever seen, not to mention the least popular candidate to win the election. He is undoubtedly facing a difficult road, and not only because he appears wholly unprepared for the job.

There are a lot of questions to be answered about this election, and there are a lot of predictions of what comes next. In democracies, majorities are rarely ever stable, and it is here that the ‘political game’ in the US will really become apparent as Trump (should) balances his minority win not only with a majority electorate, but also within his own divided base. Congressional politics will also come into play as members of Congress, up for re-election again in two years, work to figure out how to operate in their new reality. The Democrats are potentially still very much in the game, but there will be soul searching to do as they try to reclaim those votes that they lost. And these are only the questions of ‘what is next’ pertaining to the American system itself. When we look at broader questions about the future of democracy and what this win means for the international system, we encounter a whole new pack of complexities and potential consequences that must be understood.

It is certain that the analysis of Trump’s win will still be coming out many years from now. Many, like my colleague Bulent Gokay, will make the argument that together with Brexit, this election is a sign of the death of the neo-liberal capitalist world order. I think there is some validity in some of that, but I’m not entirely convinced it can explain all of the forces at work. Some will lament that this is the end of democracy. For me, that is a very premature lament and it is one that could cause a dangerous overreaction of an incited progressive left.

No, it is not the end of democracy. Yes, economic systems and practices have failed large numbers of people, and yes, people in Western states are increasingly, and detrimentally, retreating from civic life. Government has not always worked for them, or at least that is what they perceive. But voter turnout in both the UK and the US were high this year, so at least that component of democracy is firmly intact and people are having their say. Democracy may have returned a result that we do not like, and with Trump’s bombastic style and apparent disregard for the rules it is easy to see what people are fearing an authoritarian US. I would be lying if I said that was not in the back of my mind as well. But returning an unfavourable result or the election of an ‘unconventional,’ and frankly socially unacceptable, candidate does not hail the death of the system. Indeed, these results demonstrate that many who have felt ‘left behind’ by politics have made themselves heard. We may be witnessing a ‘blip’ in progressive politics, but not the death of democracy. Rather, what we are seeing is yet another step in a long history of political development that is a regular, and very healthy, process. For those of us who study political development, especially within what is commonly (yet is outdated terminology) referred to as the ‘Third World’, this process is all too apparent.

No country ever stops building or growing. And that’s because politics (the abstract system, not the parties themselves) is constantly changing. When change becomes apparent it can be incredibly turbulent, but that is because politics rests not only above but also within society; it is a structuring force but it is also a social force. Social change can be difficult and can bring backlashes against the redistribution of power and privilege from those who are still privileged and secure, but feel that they are losing power. And power is a tough thing to give up. Progressive change is perhaps the toughest of all, simply because it works to disrupt inequalities in social, and therefore, political power. When you take the power away from the people who have always had it and redistribute at least some of it amongst those who have been marginalized, those entrenched feelings of entitlement for those who have been dominant are tough to eliminate.

We see this all over the world, especially in countries where democracy is new. But from those countries, we also know that progress is not a straight line and can even be regressive at times. When we see that, we do not immediately lament the death of democracy. Instead, we say “the really important thing is what comes next.” The what comes next does not always come quickly in new democracies, but in many, the forward motion begins again and the system is stronger for it. It is when other forces come into play – damaging social forces, weak institutions, the lack of a civil society – that we begin to fear for the security of the democratic system. What we look for there is not the outcome of one election, but rather the erosion of the political and social institutions that make a democracy viable. And we are not (yet) seeing that in the United States, despite numerous observations of change.

A set back is not the end. Rather, it is likely a sign of some form of progress being made. But as always, the really important thing is what comes next.

It is incredibly important to ask the big questions of ‘Why did this happen?’ and ‘What can this tell us?’ For that reason, the social sciences, and especially International Relations and Politics, will be incredibly important in the years to come. We need to understand the systems of power that surround us both in our countries and in the wider world. We cannot focus on the ‘what if’ and the ‘what’s next’ without looking at the bigger empirical and theoretical pictures. It would be irresponsible for us to do otherwise. But we in IR and Politics also cannot do it alone, and it is for that reason that I was incredibly glad to see commentary from Mark Featherstone, our colleague in Sociology at Keele. We need to understand how power shifts impact daily lives, and a mutli-disciplinary approach is important for that. It is important for not only understanding and explaining, but it is also important for reacting and directing what comes next.

It is important for ensuring that our regressive blip does not become an insurmountable speed bump – something we have seen time and again in newer democracies. Our Western liberal democracies have the political and social institutions that have the strength to act as a check on potential authoritarian power, whether that check is direct or not. But still, we must understand this regressive blip in order to address it.

We must also not only question, but also confront, dissatisfaction based on loss of (largely social and economic) power. We must confront it because, as we’ve seen, the invocation of that fear can be ‘bigly‘ damaging (sorry, I simply could not resist). It also resides primarily with people who fear what they could lose, rather than mourning what they have already lost. We saw with the Brexit vote that many of the most ardent anti-immigration areas in the country are those those that do not have high numbers of immigrants. In the US, invoking fear of economic loss so recently experienced with the 2008 economic collapse within relatively well-off demographic groupings is a very useful political tool, and one that allows for a vote of self-preservation for a candidate that is otherwise socially and politically unacceptable. Societal shifts stemming from legislative attempts to reduce the marginalization of minority groups demonstrated a shift of power away from straight, white, Christian Americans. An out of control segment of the media did not help – one that decried the election of a black president as the ‘End of White America’, declaring that president to be a race-baiter while speaking to what was once a fringe segment that believes that the mere existence of a black man in society is all that is needed to be a damaging threat. And a mainstream media so fearful of lost revenues that they have foregone their responsibility as the ‘fourth estate’ is a tragic reality of this election.

Damage has been done, but that does not mean it is permanent.

We must understand this and we must confront these concerns. But democracy allows for that, and as long as that occurs we should not lose hope of returning to our progressive path forward. And as that happens, we can look at this and realise that democracy, no matter now old or established, is not immune from the need to constantly adapt and adjust, and that political development never stops.

Dr Rebecca Richards is a Lecturer in International Relations at Keele University. Her research focuses on statebuilding and political development. She is especially interested in how political socialisation impacts upon democratic transitions and the processes of political and institutional change.

“The spread of fascism in the 1920s was significantly aided by the fact that liberals and mainstream conservatives failed to take it seriously. Instead, they accommodated and normalised it.

The centre right is doing the same today. Brexit, Trump and the far right ascendant across Europe indicate that talk of a right-wing revolutionary moment is not exaggerated. And the French presidential election could be next on the calendar. …” These words are from a recent article in The Conversation, for the full article see https://theconversation.com/no-this-isnt-the-1930s-but-yes-this-is-fascism-68867?utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Latest%20from%20The%20Conversation%20for%20November%2016%202016%20-%206106&utm_content=Latest%20from%20The%20Conversation%20for%20November%2016%202016%20-%206106+CID_9322d0cc02d76d9ef0aa3cc26da9d98f&utm_source=campaign_monitor_uk&utm_term=No%20this%20isnt%20the%201930s%20%20but%20yes%20this%20is%20fascism

LikeLike

Exactly. And that is a serious concern in today’s global world, and one purposely ‘skirted’ in this post (mostly because it would have turned into an overly lengthy tome). However, it is also why it is more important than ever to not only re-engage with politics at all levels, but to also understand how the systems of governance around us work. Trump poses a more serious threat to American liberties and progress than many can ever remember. However, the institutions – including the institution of politics and the institution of society – can act as a check on that. It is important that we do not back down. But it is just as important that we do not overreact. Progressive change, and drastic progressive change at that, can lead to a backlash or regression, yes. It’s understandable as progressive change, by its nature, works to restructure or redistribute social, economic, and political power. But just as it is difficult to lose long entrenched power, it is also difficult for those who historically have been marginalized to give up the power they have achieved through progressive change – the silent or oppressed cannot be silent or overlooked any more. And given Trump’s popular loss and his alienation of much of the political machinery in the US, he will face significant obstacles in his time as president. The left might not be in power, but it is not weak in the US, and the almost immediate reaction of Congressional Democrats has been exactly the opposite of Labour in that the Congressional Democratic leadership is more inclusive of the wide spectrum that the party occupies – it is moving to the centre, but it is also expanding to be inclusive of an increasingly liberalised base. No, the Democratic Party is not in the shambles that Labour is in the UK. Also, despite some of the completely unacceptable individuals in Trump’s transition team, there are incredibly positive signs coming out of the US that the institutions (social and government) will not back down quietly. We see that in the UK as well, and recent news coming from France is downgrading Le Pen’s chances (http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-11-16/french-pollsters-spooked-by-trump-but-still-don-t-see-le-pen-win) – Chris Huggins has some interesting things to say about the process and politics of the French elections, which we can hopefully get him to write about here. It is still early days and now, as never before, it really is too apparent that we do not know what will happen next. So we must be aware and we must continue to challenge, to understand, and to not accommodate or normalize. We have every right to be wary and cautious. However, the outlook is not entirely pessimistic. – Becky

LikeLike